Risk Assessment and Control Design for SOC 2 Compliance

-

Last Updated:

10 Feb 2026

-

Read Time:

7 Min Read

-

Written By:

Isha Choksi

Isha Choksi

-

428

Table of Contents

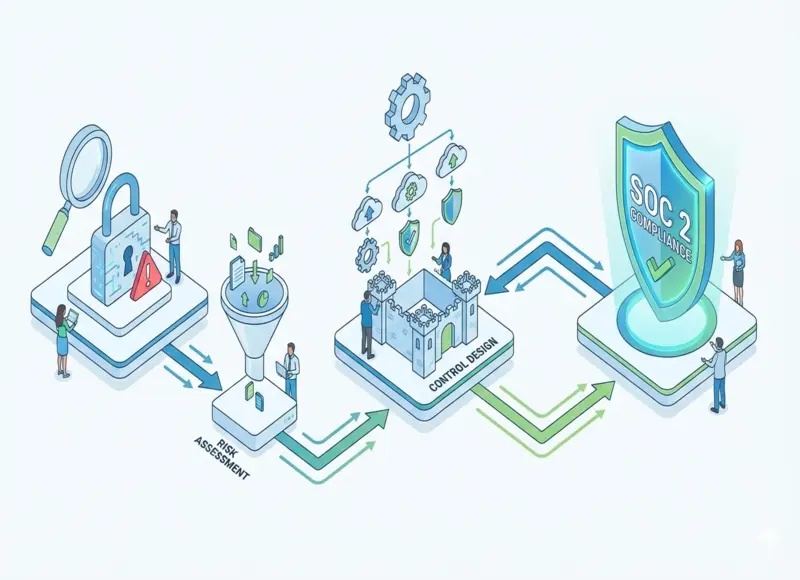

SOC 2 succeeds when risks drive control design. This article shows how to scope correctly, assess real threats, and build practical controls that fit how teams work and generate audit-ready evidence without chaos.!!

SOC 2 projects rarely fail because teams don’t care about security. They fail because the work gets framed as “writing controls” instead of building a system that reliably produces the right outcomes—and produces evidence without chaos.

When you approach SOC 2 as a documentation exercise, you end up with controls that look good on paper but break under real conditions: engineers bypass them to ship, access reviews become a spreadsheet scramble, onboarding/offboarding is inconsistent, and incidents reveal that nobody is sure who owns what. A proper risk assessment and control design process prevents that by connecting your business reality to your audit scope, your control set, and your evidence model.

The most effective SOC 2 programs begin with a simple idea: controls should reduce your real risks and match how your organization actually operates. That means your risk assessment must be specific—tied to systems, data flows, and failure scenarios—not a generic template.

And your controls must be designed like product features: clear inputs, clear outputs, clear owners, and repeatability. If a control relies on memory or heroics, it will fail the moment you scale or someone goes on vacation.

This article explains how to run a risk assessment that auditors respect and how to design controls that are both practical and defensible. You’ll learn how to set the SOC 2 scope, identify credible threats, convert those threats into control objectives, and implement controls in a way that produces evidence naturally.

You’ll also see how to avoid common pitfalls—like over-scoping, writing vague controls, or building evidence after the fact. The goal is to help you pass the audit, yes—but more importantly, to build a compliance program that strengthens trust, reduces operational risk, and doesn’t slow your teams down.

Scope the Risk Assessment the Right Way So SOC 2 Doesn’t Become Endless

Start with what SOC 2 is actually evaluating

SOC 2 is built around the AICPA Trust Services Criteria (TSC). Your auditor is not evaluating “security in general”—they’re evaluating whether the controls you claim exist actually operate effectively, consistently, and in-scope. That’s why scoping is the first decisive step.

If you scope broadly without clarity, you’ll spend months chasing controls for systems that don’t matter. If you scope too narrowly, you risk missing critical pathways where customer data or service commitments are actually delivered.

A practical scope definition usually includes: the product or service boundary, the environments that support it (production and relevant staging), the systems that store or process customer data, identity providers and access tooling, CI/CD, and the core cloud infrastructure.

It should also include key third parties that are part of your service delivery (hosting, observability, customer support platforms, payment processors, where relevant). The goal is to reflect what customers rely on—not every internal tool your company has ever used.

Build a simple system and data-flow map before you talk about controls

Many teams skip directly into “control writing” and then discover late that they didn’t understand their own boundaries. A lightweight architecture and data-flow map solves this. You want to know: where customer data enters, where it is stored, where it moves, where it is exported, and who can access it. You also want to highlight the trust boundaries: the points where identity, roles, networks, vendors, and environments intersect.

This map becomes the backbone of your risk assessment. It keeps your discussions grounded. Instead of debating abstract threats, you can ask: “What happens if this admin role is compromised?” or “How would an attacker move from support tooling into production?” That’s where real risks—and real controls—appear.

Confirm your control ownership model early

SOC 2 controls fail in practice when ownership is ambiguous. Before you design anything, decide which teams own:

- Identity and access (SSO, MFA, provisioning, privileged roles)

- Infrastructure and cloud configuration

- Application security practices

- Incident response

- Vendor and change management

- Evidence collection and control operation tracking

SOC 2 is a program, not a document. Ownership is what makes it operable.

Run a Risk Assessment That Produces Real Control Priorities

Identify risks as scenarios, not categories

Auditors will accept risk frameworks, but the most useful risk assessment is scenario-driven. Instead of “risk: unauthorized access,” define a concrete scenario like: “Attacker obtains engineer credentials and escalates privileges in cloud console, leading to data exposure.” That specificity helps you design the right controls and avoid vague wording.

Good SOC 2 risk scenarios typically include:

- Credential compromise leading to unauthorized access

- Misconfiguration exposing data publicly

- CI/CD or supply-chain compromise

- Insider misuse of privileged access

- Failure to detect incidents due to missing logging

- Availability disruption due to ransomware or outages

- Vendor compromise affecting your service

You don’t need dozens. You need the few that meaningfully represent how your service could fail.

Score risks in a way that leadership can act on

Risk scoring should help you make decisions, not fill cells. Use a consistent approach—likelihood and impact are enough. Impact should reflect what matters to customers and your commitments: data confidentiality, service availability, integrity, and compliance obligations. Likelihood should be grounded in your context: how broad your access is, how strong your identity controls are, how exposed your system is, and how mature your monitoring is.

Then connect each high-risk scenario to a control objective. For example:

- If credential compromise is a high risk, your objective is to prevent and quickly detect unauthorized access to sensitive systems.

- If misconfiguration is high risk, your objective is to enforce secure configuration baselines and detect drift.

This mapping is what keeps SOC 2 from becoming a generic checklist. It becomes a tailored system of controls driven by your risks.

Use “risk treatment decisions” to avoid control bloat

One of the biggest SOC 2 mistakes is writing controls for everything because “it might come up.” Instead, document risk treatment decisions. For each scenario, decide whether you will mitigate, transfer, accept, or avoid the risk—and document why. Auditors don’t require zero risk. They require that you understand your risks and have rational, operating responses.

This is also how you keep scope stable. If a system is out-of-scope and doesn’t affect service commitments, document that decision. If you rely on a vendor’s SOC report, document how you evaluate it. These decisions reduce chaos during audit prep.

Design Controls That Actually Operate and Produce Evidence Naturally

Write controls as operational mechanisms, not policy statements

A strong SOC 2 control is not “We ensure access is appropriate.” That’s an intention, not a mechanism. A real control describes who does what, how often, using what system, and what evidence is produced. Think in “inputs → process → output” terms.

For example, instead of a vague access control statement, define something like: “All production access is provisioned through the identity provider with role-based groups; privileged roles require MFA; access is reviewed quarterly by system owners; terminations trigger automated deprovisioning within X hours.” This is measurable, testable, and easy to evidence.

Design controls around the way work already happens

Controls are easiest to operate when they align with existing workflows. If engineers already use pull requests, build change management controls around PR approvals, branch protections, and CI checks. If onboarding is already in an HR system, connect identity provisioning to that workflow. If incident response is already managed in a ticketing system, use that as your evidence trail.

When controls fight reality, people work around them. Auditors may not see the workaround immediately, but it will surface eventually—often during an incident or a Type II period when consistency matters.

Build an evidence model at the same time you build controls

Evidence is not a last-minute scramble if you design it early. For each control, define:

- What evidence proves it operated (logs, tickets, screenshots, reports)

- Where that evidence lives

- Who owns collecting or generating it

- How often is it produced

- How do you ensure it is complete

A useful trick is to favor system-generated evidence (IdP reports, CI/CD logs, cloud audit logs) over manually assembled evidence. Manual evidence is fragile and inconsistent. System evidence scales.

Validate controls with a short “pre-audit” test run

Before the official audit period (especially for Type II), run a short internal test: pick a sample and verify you can produce evidence quickly and consistently. This reveals weak controls early—like access reviews that aren’t actually happening or logging that isn’t retained long enough. Fixing these before the audit window is far cheaper than repairing them mid-period.

Know when expert help prevents rework

SOC 2 becomes expensive when teams redesign controls multiple times, over-scope unnecessarily, or discover late that evidence doesn’t meet audit expectations. This is where soc2 consulting services can be valuable—particularly for designing a lean, audit-ready control set, mapping risks to the Trust Services Criteria cleanly, and establishing an evidence collection workflow that won’t collapse during a Type II period. The goal isn’t to outsource responsibility; it’s to avoid building the wrong program and paying twice.

Conclusion

Risk assessment and control design are the backbone of SOC 2 compliance. If you do them well, the audit becomes a structured verification of a program you already run. If you do them poorly, the audit becomes a stressful game of catching up—writing controls after the fact, collecting evidence retroactively, and trying to keep inconsistent processes from showing through.

The most effective approach starts with scoping that reflects your real service boundary and the systems that support customer trust. From there, a scenario-driven risk assessment turns abstract requirements into concrete priorities: credential compromise, misconfiguration, detection gaps, vendor exposure, and operational disruption.

Each priority becomes a control objective, and each control objective becomes a mechanism that can operate reliably—without heroics. Controls should be written in a way that’s testable, repeatable, and naturally produces evidence through the systems your teams already use.

Recent Blogs

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Modern Law Firm Growth Strategies

-

03 Mar 2026

-

6 Min

-

88

How Custom Software Companies Help Enterprises Automate Complex Workflows

-

03 Mar 2026

-

5 Min

-

96